Macron hoped the Baghdad conference would launch his ambitions as a regional mediator. But Iraqi and US officials think the French just don’t have the clout

This piece was originally published on the middleeasteye website https://www.middleeasteye.net/

In Baghdad, the clock is ticking.

The United States has promised to pull its forces from Iraq by the end of the year, with several people wondering who will – or can – fill the void left by Washington.

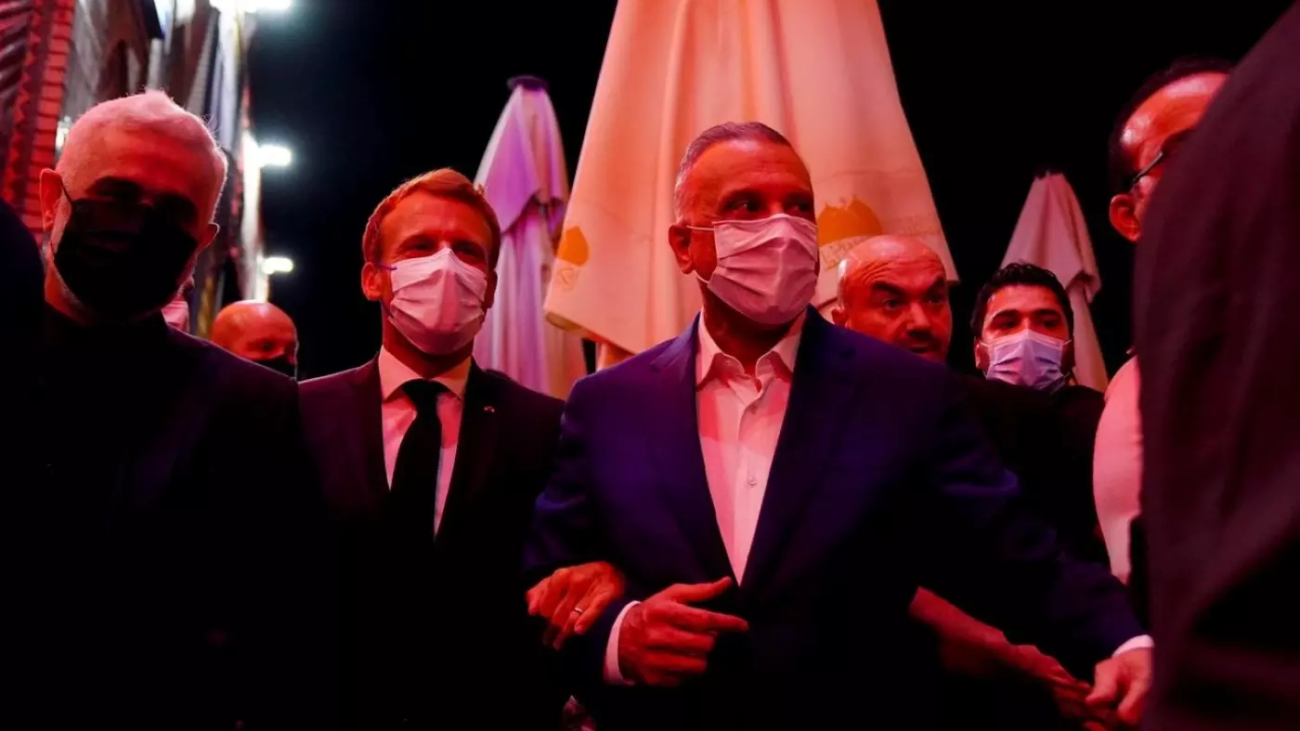

Last weekend, while attending a regional summit in the Iraqi capital, Emmanuel Macron began to make the case for France.

The French president wants to present Paris as a supporter and strategic ally of the Baghdad government, Iraqi and US officials told Middle East Eye. A regional summit in Iraq’s capital was a perfect place to start.

Iraqi-French relations are considered good and stable.

‘Iraq is close to Turkey and France is looking for cards to pressure Turkey and strengthen its position in its ongoing conflict in the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa’

– Elie Abouaoun, analyst

France was among the first countries that recognised the new political system, despite its refusal to participate in the international military coalition led by the United States to topple Saddam Hussein in 2003.

And it comes second only to the US in the number of personnel deployed in Iraq as part of the international coalition against the Islamic State (IS) group, as well as being a key Nato member.

For France, the planned US withdrawal is a chance to dig its heels into Iraq and establish a launching pad to expand its influence in the Middle East, provide balance to Iranian influence, and compete with Turkey, a Nato ally it is often at odds with.

The French believe that after decades of war, weakness, and tumult, Iraq is ready to receive them, and will provide them with a base to build political and economic bridges with the countries of the region, Iraqi officials said.

The Baghdad Conference on Partnership and Cooperation, held last weekend, witnessed the launch of this plan. It was “the official gate” through which France entered Iraq to introduce itself as “a partner to the Iraqi government in its concerns and a sponsor of Iraq’s regional and international interests”, as one Iraqi official put it.

At the conference, Macron said in a televised press conference that France will maintain its presence in Iraq to fight against terrorism, “no matter what choices the Americans make”.

“It is clear that France sees the American retreat as an opportunity to gain political and economic influence in Iraq, after its failure in Lebanon,” Elie Abouaoun, director of Middle East and North Africa programmes in the United States Institution of Peace, told MEE.

Last year, Macron made a bold intervention in Lebanon following the August Beirut explosion, promising to find a way out of the country’s political and economic malaise, but instead found Lebanese leaders as intransigent as they were before the catastrophic blast.

Meanwhile, France has argued with Turkey on several issues, including the strategic and gas-rich eastern Mediterranean and Libya, where Ankara and Paris backed opposing sides during the recent war.

“Iraq is close to Turkey, and France is looking for cards to pressure Turkey and strengthen its position in its ongoing conflict in the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa,” Abouaoun added.

“France has an agenda and is pursuing its lines.”

The French project

According to Iraqi officials, the Baghdad Conference was originally a French project.

It was based on an idea adopted by former Iraqi prime minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi and was raised for discussion by Iraqi President Barham Salih during a visit to France in February 2019.

Although Abdul-Mahdi visited France three months later to mature the idea, he later abandoned it and pivoted towards China, “for fear of being accused of falling into the arms of France, as he has French citizenship and because he is not accepted regionally”, an Iraqi official familiar with the project told MEE.

“The original idea was to find an alternative strategic ally for Iraq to replace the United States after its withdrawal,” another senior Iraqi official told MEE.

Many political forces, including some backed by Iran, are concerned about the idea of a total US withdrawal from Iraq.

Iraqi leaders “were and still are looking for a force that could secure an objective balance against Iranian influence in Iraq and the region”, the senior official added.

“No one wants to fall completely into the Iranian quagmire. The Iranians themselves do not want to be responsible for everything that happens in Iraq and are looking for partners in the spoils and losses.”

The French seized on Abdul-Mahdi’s idea, developed it, and then put it forward as an initiative entitled “Supporting Iraq’s Sovereignty”, which was announced by Macron during his previous visit to Iraq in September 2020.

This conference was supposed to be held in Paris, as the French wanted to be the event’s organisers.

However, after the conference expanded to include a number of regional rivals, it was moved to Baghdad and reworked as an event focusing on stability in the Middle East.

“Although France, practically, has nothing to do with the conference in its final form, and its participation was not justified, the Iraqis could not exclude them because they had the original idea,” a member of Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s team told MEE.

“Iraq wants to return to playing the role of mediator, and the French wanted this conference to be a ticket for their return to the region through Iraq, so it became a kind of servitude between the two parties,” he added.

“France was presented as a co-chair of the conference, but the truth is that the Iraqis were the ones who organised everything, and the gathering of all these [participating countries] was the fruits of Kadhimi’s efforts and relationships.”

The French foreign ministry did not reply to questions sent by Middle East Eye before the time of publication.

The anarchy

The dramatic US withdrawal from Afghanistan last month and the swift Taliban takeover have cast a heavy shadow over the political scene in Iraq and raised fears of a number of Iraqi political forces that a repeat scenario could appear in Iraq.

The worst-case scenario for most political forces not associated with Iran is what they call “numerous anarchy”. This would lead, they believe, to the outbreak of intra-Shia and intra-Kurdish fighting.

Such conflict would eventually lead to the country’s politics being divided strictly down sectarian and ethnic lines, they believe.

“The political system in Iraq did not derive its legitimacy from the elections. It derives it from the legitimacy that the international community bestows upon it,” another member of Kadhimi’s team told MEE.

“Threatening the legitimacy of this regime by bringing the United States and the international community to the conclusion that Iraq has become a lost cause and that there is no point in continuing to support it, will mean the collapse of this regime and the transformation of Iraq into a state of sects,” he warned.

‘The political system in Iraq did not derive its legitimacy from the elections. It derives it from the legitimacy that the international community bestows upon it’

– Member of Kadhimi’s team

“A complete American withdrawal, with Iran losing control of its proxies inside Iraq, will necessarily lead to massive political and popular chaos. This chaos means the outbreak of a bloody conflict between sectarian and political groups. The partition of Iraq may be the inevitable result of this level of conflict.”

The majority of Iraqi politicians and officials are nowhere near this pessimistic, however.

Such an anarchic scenario is deemed unlikely because most Iraqi political forces have been aware of the upcoming challenges a US withdrawal will bring and have been working to find alternative sources of power to create a balance.

Among the most prominent of these forces are Muqtada al-Sadr’s movement, al-Hikma Movement led by Ammar al-Hakim, former prime minister Haider al-Abadi’s al-Nassir Alliance, and a number of forces close to Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani, in addition to Kadhimi and Salih.

“These represent the nucleus of a major political alliance that may be formed after the October parliamentary elections to form the largest bloc and name the next prime minister,” an al-Hikma leader told MEE.

“These forces will lead Iraq towards consolidating its sovereignty and gradually getting out of the cloak of Iran, while trying to find an alternative to the United States to create the required balance in Iraq and the region.

“France is a regionally accepted international player, it is the second power in the European Union and is not rejected by Iran, which is very important.”

Baghdad is just one step on the road

Though Tehran and Washington have maintained a fierce grip on Iraq since 2003, they are no longer as popular and politically influential as before, officials and politicians said.

With the United States seemingly retreating from the region, Iraqi politicians and officials want to establish a state of equilibrium in their country, which they believe could be achieved by turning Iraq into “a meeting point” for the regional players. This could “enhance the strength and influence” of a number of regional and international powers by creating common interests with Iraq at the centre, US and Iraqi officials said.

“Iraq seeks to portray itself as a key player in the region. Many Iraqi governments have sought to take this role previously. Kadhimi made great efforts for Iraq to play a positive regional role,” Douglas A Silliman, US ambassador in Baghdad until 2019, told MEE.

‘Iraq seeks to portray itself as a key player in the region. Many Iraqi governments have sought to take this role previously.’

– Douglas A. Silliman, former US ambassador

“The stability of Iraq can be the basis for the stability and prosperity of the region.”

Kadhimi began preparing for the Baghdad Conference by making arrangements with Egypt’s President Abdel Fatteh el-Sisi and King Abdullah II of Jordan, then expanding to include Iran, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and other countries.

“This role is very important for Iraq in terms of geopolitics,” Silliman said.

“The idea is for Iraq to be an area of consensus and stability for the countries of the region, instead of being an area of conflict, as happened over the past years.

“The most important thing that was achieved in this summit was the small bilateral meetings that took place on the sidelines of the Baghdad conference. The conference created the appropriate ground and atmosphere to start dialogues between the conflicting parties, and this is what is important.”

Too much control

The Taliban takeover and haphazard US retreat in Afghanistan have been hailed by Iran and its regional proxies as a blatant American defeat and a great victory for Islam. They have promised the same will be seen in Iraq once the US pulls out from there, too.

Publicizing such an outcome has alarmed many Iraqis. Yet Iraqi and US political leaders and officials have ruled out a repetition of Afghanistan and ridiculed the idea that Iran-backed factions will soon be in charge and pursue anyone deemed agents of the US and the West.

“Actually, the Iranian-backed armed factions can bring down the government and take control over Baghdad within days, if not hours, but they will not,” a prominent Shia politician close to Iran told MEE.

“The current situation serves Iran and its proxies more than anything else. Therefore they will not even repeat the experience of bringing a prime minister who is completely loyal to Iran, as happened with Abdul-Mahdi,” he added.

“The situation in Iraq is totally different compared to Afghanistan. The commanders of armed factions and politicians associated with Iran totally understand this, so they do not even seek to formally control the government or any other governmental departments.”

In fact, any full takeover by Iran and its proxies would immediately spell financial ruin for Iraq.

All Central Bank of Iraq reserves and funds obtained from oil sales have been deposited directly into special accounts in the US Federal Bank, and have been covered by US immunity since 2004, to prevent creditor countries from pursuing and seizing Iraqi funds.

The Iranian-backed forces fear that the United States could then freeze Iraq’s assets and impose financial sanctions that could topple any government they have established within weeks, politicians and officials said.

On top of that, Iraq has a hugely fractured political landscape, and growing conflicts between Iran-backed armed factions. So, finding some sort of unified position that could assume supremacy after the US pulls out – as the Taliban has done – is supremely unlikely.

Meanwhile, there is trepidation about what stance Sistani, the supreme authority of the Shia community in Iraq, would take, as he could end the paramilitaries’ hopes and much of their popular support in an instant.

Time to lower expectations

Quite simply, Washington’s withdrawal from Iraq will not resemble its pullout from Afghanistan.

The United States has agreed with the Iraqi government to withdraw all combat forces by the end of December, but Washington will still provide intelligence and air support to Iraq.

Most importantly, the agreement signed between the Kadhimi government and the Biden administration allows the US forces to carry out military operations inside Iraq if the Iraqi government so requests, US and Iraqi officials told MEE.

“All military operations in which US forces participate will cease by the end of 2021, but if the Iraqi government needs assistance, such as aviation or intelligence, it will be provided from outside Iraq,” a US official familiar with the details of the agreement told MEE.

“Analysis of intelligence, combat aircraft, and drones do not need to be physically on the ground… [Therefore] we accepted Kadhimi’s proposal to withdraw the remaining combat forces in Iraq, even though their numbers do not exceed dozens.”

For France, the future in Iraq is likely not to be as rosy as it wants to believe.

Politicians and officials told MEE that ultimately, Paris just doesn’t have the right ingredients for success in the short term.

The United States, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other countries that have real influence in Iraq have invested a lot of money and built strong relationships over the past two decades. Late entrant France cannot boast that it has done the same.

“The French will not succeed in filling the vacuum that the United States may leave in Iraq. They are only seeking to turn the available space into a foothold for expansion in the Middle East,” one of Kadhimi’s team members told MEE.

“The region, from the point of view of the French, is now ripe and ready to receive them because the Iraqis are exhausted and their country is in ruins, Syria is in ruins and Yemen is almost in ruins, and this means that there are about 250 million people who need to build politically and financially.”

The source noted that Kadhimi allowed French participation in the Baghdad Conference out of respect for France’s role in setting it up in the first place. But essentially the conference was more about establishing Kadhimi as the regional mediator and winning him a second term in power, not Macron.

“To what extent will any of them succeed, this is what the coming days will answer.”